Now this is real journalism.

Filmmaker D.B. presents us with an essay on the state of film, streaming and A.I. that is absolutely essential reading for everyone.

This impeccably researched and argued work deserves to be read carefully and then spread far and wide. I’m biased but for me this is better than virtually all of the quality legacy media discussions on tech and cinema today, let alone all of the hot takes from the ill-informed and professionally outraged.

Enjoy

TJB.

“Filmmaking is just a constant scramble for resources.” ~A friend.

Two necessary disclosures: 1) I am not a member of the WGA or SAG-AFTRA, nor related studio motion picture industry unions, and cannot speak for their official positions. 2) The ongoing strikes are dynamic and many of the specifics may change by the time this essay is published. For the official statements of the striking unions, visit the WGA Strike Hub and sagaftrastrike.org .

I am an independent filmmaker with a dream of ‘making it’ one day, which means having the opportunities and resources available to write and direct feature-length narrative films that can be sold to interested viewers in a commercial market. I go into this ambition clear-eyed that film production is a prestige industry with a steep Pareto distribution in which very few people get the bulk of the resources, attention, fame, glory, and above all financing to make their dream productions, on top of a wide base of largely working class and lower income workers who pay their bills off of a volatile gig economy.

I have the additional challenge of being inclined toward weird, fringe ideas inspired by weird, fringe, mostly unprofitable movies. I pair my concern that my movies are necessarily limited in audience with the insistence that that audience exists. If the audience is small, it requires the movies cost less1.

Working in independent film means being squeezed between the vice clamp of a studio system uninterested in your work unless it can sell merchandise, and a critical and impatient audience that has its expectations framed by the production values and advertising strength of that same studio system.

On the other hand, independent filmmakers like me are motivated to carry on because independent film has always existed and filmmakers have found their audience somehow. Even while audiences are rolling their eyes at bankrupt movie theatre marquees saying “Psh, Hollywood doesn’t have any original ideas anymore,” more independent films are being produced on a yearly basis than ever before.

This essay, then, is about platforms versus access and what they cost to filmmakers and viewers alike.

The last time the WGA and SAG-AFTRA striked together, it was over residuals for television2. The 1980 SAG strike was over residuals for home-video and on-demand. The current WGA / SAG-AFTRA strike is largely about residuals from online streaming and AI. AI generative algorithms are just an expanded use of distributing original content and people’s likeness through a newer medium. I will go into detail below.

Thus, any time a new distribution medium is developed, the studios use that opportunity to cut the rates given to both old and new makers of intellectual property. Their excuse is always that the audience pays less for it – television viewers don’t pay ticket prices to access a broadcast, streaming subscribers only pay a small fixed rate for a library of content, AI is ‘just a search engine’ etc. Meanwhile the audience wants the deepest possible library of content for the cheapest possible price.

However that overall approach lands us in the quality - expense - convenience triangle:

A Non-Nostalgic Look at the Access and Choice We Recently Had:

I just counted. When I turn on my profile on Netflix, it takes about four rows of sorted titles before the rows largely show repeated thumbnails. By the time I’ve gone through those four rows, I counted just over 200 movies or television showss, 60 which I’ve already seen. Yes, if I keep going, subsequent rows show more selections at a quickly diminishing pace, so I can say the front screen probably shows maybe 500 movies. Maybe. Scrolling through it is tough, but not because of too many options, but because too many repeats.

Meanwhile, whatsonnetflix.com lists 4165 available options. My profile is only given 12% of the library. In order to find the rest, I have to search for the titles one by one, and to search for them, I basically have to know it’s already there3.

It may be unwieldy to dump 4165 titles on an audience’s head, but one thing I’ve never understood is why Netflix has no “Browse All” function. Or why I can’t purge listings I’ve already seen from my profile to have new ones appear. Perhaps even have a choice to hide a movie temporarily to repopulate later, when I may be interested in revisiting it, versus some movies on my list I can assure you I have no interest in watching.

But more importantly, 500 titles is far less than 4165, and 4165 is far less titles than were available to me when I used to work at a video rental store. Blockbuster started with 8000-10000 rental units, and those were bulky VHS tapes4. There was an amazing period in the late 2000s where almost any movie you could think of was available at stores like Hastings. If those tens of thousands of titles were too restrictive for you, you could find more on Netflix’s red-envelope mailing service; and if Netflix didn’t have a particular disc, you could special order or buy it from Amazon.

Let me illustrate this specifically: I’d end up stumbling across a rental of Bill Morrison’s Decasia about the same time I was tracking down Jiri Trnka’s puppet animations and collecting DVDs from Other Digital: These were things I found on shelves. Absolutely dusty, tiny-section-near-the-back shelves, but they were there. The stores could afford to have them on the shelves, because they made enough money from tons of mainstream rentals that it allowed for a few specialty shelves..

Once the shelves started getting too full at Hastings, we’d print out a list of movies that hadn’t rented in over six months5 and put them into a sale discount bin. In retrospect, that is a peculiarly interesting process of curation, because it gave everything the chance to be found and rented but also acknowledged that some titles just weren’t rented enough for the real estate.

If people kept asking for a movie we didn’t have to rent, we used our best judgment to make a rental of it. This made the selections regional: our rental store was located in the Southwest, so we always had multiple copies of the independent film Mi Vida Loca rented out. My specific store was near to the university area, so its foreign and drama sections were relatively sizable in comparison to partner stores in other parts of the city.

Meanwhile, streaming was growing, studios were digging ever deeper into their vaults for more content, DVD sales were saving television shows that were imperfectly scheduled from cancellation, and some studies offered manufacture-on-demand DVDs of some of their more obscure golden age productions.

All of this leads to the assumption that ever-cheapening costs of distribution in the digital era would create a long tail benefit to filmmakers and distributors. Everything would be available all the time, so some initial flops had the capacity to make their money back over time, audience attention otherwise equal. If someone discovered an obscure movie they liked and did a little research, they could end up going down a rabbit hole of film discovery.

Now rental stores are nearly extinct, DVDs are barely sold anywhere and are increasingly out of print, Netflix is shutting down their red envelope service, and their current catalog doesn’t offer any movie made before 19466.

You, my reader, have barely a smidgen of the choice and variety you used to have in movies available. That choice has been taken from you.

Hollowed Out Quantities

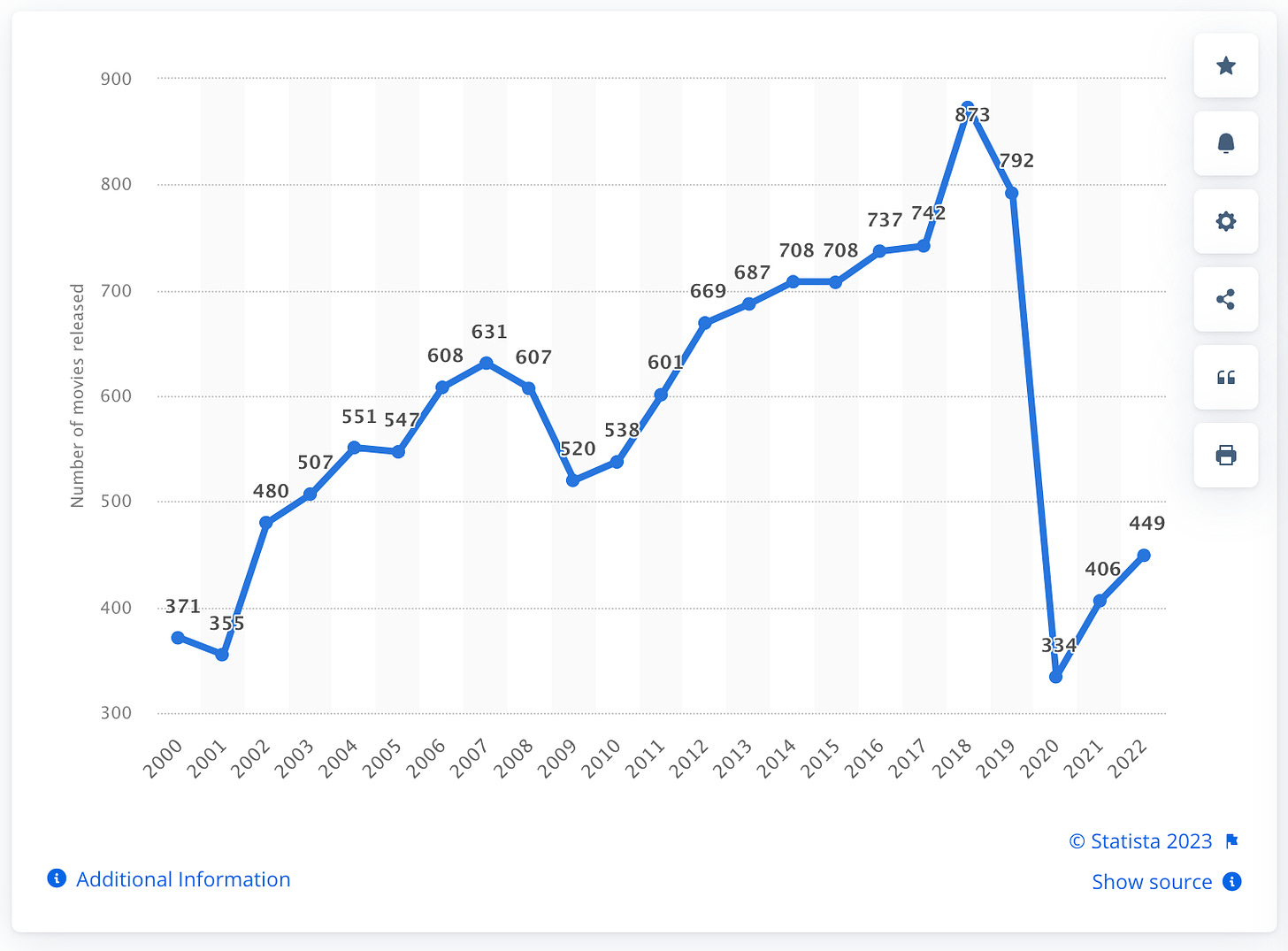

And yet, until the pandemic, more movies have been made on a yearly basis than ever before.

https://www.statista.com/statistics/187122/movie-releases-in-north-america-since-2001/7

Much of this rush of production was attributable to streaming platforms’ pivot to exclusive content to shore up their libraries. It’s sort of strange for audiences to be bemoaning no new ideas and filmmakers to be bemoaning no good opportunities when so many new films are being made, right?

Streaming doesn’t pay.

That’s the tl;dr of the WGA / SAG-AFTRA strikes, but it’s also the reason why the audience is receiving such disappointing content. Hollowed out production equals hollowed out product.

Here’s the model that filmmakers (and laypeople) generally expect for creative work to provide income: you invest your time and resources into producing IP, sell it to a distributor with a contract that gives you some payment up front, some payment on the backend of sales. As you make either really successful IP or at least build up a library of IP over time, the front-end payments keep you alive to make more work and the back-end payments give you a cushion and build over time. Ideally this grows your resources so you can do more ambitious work, or “quit your day job” and focus on the creative work exclusively. Hell… maybe even retire.

So a SAG actor who gets a small speaking role in a few episodes of Law & Order gets their paycheck for the days they show up on set, but as those episodes are bought by DVD distributors or networks for reruns or foreign markets, the actor may at least pay the electrical bill while they audition for new roles using their Law & Order footage on their showreel.

The same is true with screenwriting. Writers would pitch shows on new episodes or attempt to write new concept scripts that could be optioned and maybe, as is the goal, produced. If the options kept renewing or the produced show or movie kept being distributed, the writers could get enough income to pay their electricity bill to keep the computer humming while they took the leap on the next script.

Even in that standard model, a creative career takes a ton of risk, and not everybody can make it. The terms of IP contracts are highly variable to things like your own due diligence, your pull or strength as a recognizable talent, and whether you have good agents and lawyers.

This idea has not been realized in the world of streaming for a couple of reasons. One is that streamers’ residuals are fractions of pennies for hundreds of hours of viewing time, as opposed to pennies per box office receipt, DVD purchase, or televised rerun. The other is that streaming services refuse to offer a standardized reporting system like Nielsen ratings for television or box office / point-of-sale receipts for tickets or DVDs.

With no assessment system for how much residuals should really be owed, streamers frequently producing their own exclusive content, and streamers hiding other content under algorithmic recommendation engines, median writers’ pay has been declining over the last decade. SAG actors are seeing nothing back from hugely viral shows.

Add the cheaper production costs of digital cinema and the flood of content, the gig economy of filmmaking has become much less sustainable for most film workers.

A personal example: as an editor, when I charge a ‘day rate’ for editing, I need to charge enough to cover the days I am hunting for jobs to edit. Cheap digital editing systems have saturated the market with editors, so it’s understandable that competitive rates would go down – I can’t fight the demand / supply curve with wishful thinking. But if I did edit a feature length film that became a major box-office hit, I should get some residuals to help tide me over. If it was a huge hit on a streaming platform, even a hit that lead to a surge in subscriptions, even if more people watch the movie than would have seen it in a movie theater, I’d probably not see a dime.

Speaking of the box office blockbuster, streaming has hollowed that out, too. When the audience can get thousands of movies on giant high definition screens at home for a dozen bucks per month, then the only people who are going to pay $20 for a single movie ticket on the big screen are there for personal attachment to the public cinema experience.

With far fewer people seeing far fewer movies, studios have less room to take risk. With less room to take risk, they double-down on proven franchises. To keep the franchises proven, they also need to risk-proof them.

The Marvel Cinematic Universe is better understood if you know the history of the Sam Raimi Spiderman trilogy. Until Spiderman, comic book movies essentially never made money unless they starred Batman or Superman. Raimi’s Spiderman trilogy was also like Lord of the Rings and The Matrix in the sense that the full trilogy was contracted for scale rather than each sequel being greenlit separately.

Despite the trilogy’s financial success, the sequels were plagued with production difficulties arising from those contracts. The actors and crew got burnt out by the third movie, and Raimi and Tobey Maguire didn’t get along with each other. The financial successes of the individual entries didn’t translate to better contracts for the overall crew.

Part of the overall plan behind the Marvel Cinematic Universe is that you could keep Spiderman, but messy production stuff like keeping the same director or actor could be removed. From the studios’ perspective, better to have Spiderman get buts in seats than Sam Raimi or Tobey Macguire. This is a sea change from the celebrity-first box office draw the studios have relied on since Clara Bow.

Whereas it may be hard to imagine Tony Stark being performed by someone other than Robert Downey, Jr, if you look at things like the revolving cast of Hulks and the parade of Batmans in the new Flash movie, the studios have made it clear: any of these guys can be swapped out without over-reliance on continuity because *handwave* multiverse mumble mumble. And Flash featured performers Adam West, Christopher Reeves, George Reeves, and Jay Gerrick through deepfake technology. Easier not to pay a day rate if the person is dead.

What Your Face and Thoughts are Worth

AI seems to be the straw that broke the camel’s back.

One of the loudest sticking points in the SAG-AFTRA negotiations is that studios were offering background extras only $200 to digitally scan themselves to be included in backgrounds of movies with no expiry date. A background extra would normally expect to get paid $200 per day across various productions and hopefully be chose for a speaking role or more meaningful interaction with the characters to be a featured extra that is a bridge to SAG membership and higher rates. If they choose to just be scanned once and never used, those opportunities disappear forever – not just for them, but for all other background extras!

Disney’s already jumped in with (seemingly) creating AI generated extras in the film Prom Pact. This is going to continue and no agreement SAG-AFTRA comes to will change that.

Now. Digital background extras are already a thing. In 1982, Gandhi broke the record for most extras with 300,000 people. By the early 2000s, Peter Jackson was populating broad swathes of Middle Earth battlefields with far more than 300,000 digital figures rendered through a 3D program called Massive. Braveheart BTS lore is replete with entire battle scenes having to be reshot because camera people kept finding extras wearing digital watches – imagine how hard it would be extras in a modern war epic off cellphones.

But the studios offering $200 flat fee for someone’s likeness for perpetuity is a very strong statement on what they honestly believe a person’s likeness is worth. When you consider Disney’s strong history of IP rights management and defense, it’s clear that corporations strongly believe a person’s IP should make the corporation money for 75 years but never make the original person money at all.

SAG-AFTRA won’t be able to reverse the digitization of extras, but they have a strong position in arguing that a person’s likeness deserves more than a one-time $200 fee. If it were a one-time payment to go into a database, and then an additional payment every time someone’s likeness was selected plus royalties, plus an expiry date on its usage so that the studios of 2123 aren’t mining the same century-old visages, then I could see a reasonable discussion of how much a person’s likeness is worth. Under the current offer, a person’s own face is basically worthless, forever. Even stock footage libraries pay better than that.

It’s barely a hop and a skip before you rig the scan for animation (MoCap facial and skeleton rigs are practically drag-and-drop templates at this point, with minor adjustments for specific anatomy) and record a few voices (already well advanced in AI), first replacing featured extras and then advancing into more and more roles. Then, well, why hire a new Spiderman? You already have a digital model and audience-approved voice for perpetuity.

Someone might sign off on a $200 scan thinking, “Cool, maybe one day I’ll see myself flying an X-Wing in a Star Wars movie!” only to, not many years later, see themselves having a meaningful role in a movie that earned billions of dollars and not seeing a penny in return. And the problem is there’s plenty of people who would still think that ‘cool’ without understanding that they are, or at least should be, owed a lot of money because their own selves are being used for someone else’s profits.

And that’s before we get into the issue of whether the likenesses are used for things the original person may not appreciate, like pornography, political campaign ads, or testimonials for products they’d never use. If you think a studio isn’t going to sell their libraries of scanned models to other companies for some extra income, you don’t know how most major tech corporations make their business.

This issue is not relegated to the film industry. The current strike is merely Brownian motion for the underlying neglect of digital personhood and privacy rights in the modern era. We have not yet figured out a meaningful and fair way for human beings either individually or collectively to have control of or even benefit from the use of their own likeness and data, largely because digital information is extremely frictionless and enough people are willing to participate without compensation. But above all people don’t seem to understand how much and how broadly that volunteered information is used without their consent or knowledge.

Hollywood’s debate on this is too particular – society itself, American, Western, and worldwide, needs a fundamental reworking of digital rights and IP management to enable a person share their information or likeness with clear contracts that specify their use-cases and portion of revenues.

But the immense difficulty in communicating and coordinating that rethink with the public and forcing a change in law and regulation, particularly while the frictionlessness of digital likeness grows by magnitudes on a yearly basis, means that SAG-AFTRA and the WGA can only focus on the on IP-generating efforts of working creatives in the motion picture industry.

The WGA has a similar investment in this issue, regarding the concept of authorship. Like the workflow for swapping a few extras into actual performers’ places, Hollywood has been straightforward about their long-term intentions. If you wonder why the writing in modern movies is so bad, it’s because they hire writers, plural, while trying to get away from authors of screenplays.

People complain about ‘writing by committee,’ but it’s important to distinguish that complaint from a writer’s room. A writer’s room is lead by a head writer or showrunner who has an overall vision of the production but needs other people to nail down specific parts of it. This is mostly a television thing, which requires hundreds to thousands of pages of scriptwriting over the course of a season.

‘Writing by committee’ doesn’t have a specific format but is basically a when a studio decides they want specific elements to show up in the movie for demographic or marketing reasons, and then hire a few writers to fill in the blanks. The act of writing in beats merely to tie together disparate elements is literally called a contrivance. A writing workflow that requires writers only focus on contriving scenarios together is obviously going to result in contrived plots.

The thing about AI text generators is, they contrive on a minimally viable level. It’s work for a creative person or team to put together not only a large idea, but all of the elements that cohere with that idea to make a good story. It’s not really difficult to throw together a few scenes and set-ups and then link them together, reducing the overall quality of the story.

Writing-by-committee enables the studios to pay each writer less, as they write less content and offer less individual ideas, which in turn reduces their contributions and their residuals. Put in a widget that removes the effort needed to contrive plots, and studio movies could eventually be literally codeable: “We need a superhero movie that involves an alien god who protects the human race against a vengeful billionaire; the alien god has a sidekick that is gay and a love interest he works with; make sure the alien god and the love interest kiss at the 70 minute mark; make sure the villain kidnaps the love interest.”

Yes, initial outputs may not be enough, but then you run certain scenes through the generator again, checking off the results until you have a viable movie.

Like the issue with the digital extras, the idea that studios, or individual writers, or even specialist “AI whisperers” who are good at pulling out conspicuously interesting results can be banned or prevented from using these tools would be delusional. But what I understand the WGA is currently asking for is that at least one person is registered responsible for the final output and shares in its success. This could take the form of an AI whisperer who just excels at conjuring successful scripts out her own personal workflow of text generators, or it could be something like a showrunner who has a clear idea of what the final idea is supposed to look like and hires writers or uses text generators as is necessary, but can claim with a straight face that the end result is the story she wants told.

Paying for the Input Rather than Obscuring the Output

Like the issue of the $200 likeness, text generation algorithms fill out their neural networks on the basis of ingested text. An individual writer should be compensated with residuals if they are submitted to a large language learning model in order to include their ‘style.’ Thus far that form of digital rights management doesn’t exist, and is also a larger problem than Hollywood unions alone can handle.

Your own social media posts shouldn’t be free for a corporation to feed into an algorithm in order to undercut a professional writer’s rate.

This is why I introduced the concept at the beginning of royalties for AI work. Ultimately AI is not an alien brain generating texts or images from its own imagination. Neural networks and large language learning models input real people’s intellectual property and output that intellectual property when prompted by someone using the program. The novelness of the output is merely how the IP is reformatted to fit the parameters of the user’s prompts.

If those output prompts are then used to create a massive blockbuster movie, then the original IP that fed the model used should earn residuals up to a certain point.

I am well aware that with how massive LLMs and image generators are in terms of the amount of content they’ve already ingested, such a digital rights management protocol seems unfeasible. It’s not. It’s completely doable. We just have to recognize that AI generation algorithms are platforms that distribute content and that original content is made by people and thus fundamentally traceable to origin. Feasible isn’t the same as practical, as the outputs combine enormous and diverse sources of content that would take ages and prohibitively expensive man-hours to unwind.

But, provided there are contractual obligations among distributors, producers, and creatives that residuals and IP rights are maintained up to a certain point, then AI generative models can be built with respect to those contractual obligations, and models that aren’t built with contractual obligations can be individually prohibited. In other words, some sort of WarnerBrothersGPT could be used whereas ChatGPT is banned, Disney animators can tap into Mick-E but are prohibited from using Dall-E. This approach overcomes the “you can’t stop people using tools!” argument with “yes, but you can make sure the tools benefit its users fairly.”

Meanwhile, governments need to develop better frameworks for digital personhood so that tech companies compensate their users and sources for the use of their likenesses and creative work. And the term ‘creative work’ is generally broad and includes even social media posts and memes.

Cynics may claim such contracts or regulations are impossible but they’re absolutely possible. It comes down to political will. In the narrow politics of film and television production, that political will has translated to the WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes. Those strikes can be a starting point for something larger, or the strikes could be helped if a larger general digital rights management framework was adopted society-wide.

Either way, there’s a ton of low-hanging fruit to reach for, and it starts with understanding that human beings are entitled to control and compensation of their own likeness and creative work, and that volunteering to offer their likeness or IP to any one platform for free or cheap (like a blog post or a digital scan of your face) should not allow any private entity to use the likeness or IP for profit for perpetuity.

The Hidden Costs to Your Cheap Subscriptions

I maintain a digital rights management framework is possible. Obviously it’s not likely.

In the meantime, we still have the audience, who wants a massive volume of good quality content for very cheap (or endless great content for free). How do we support the production of creative work so that creative workers can focus their efforts on delivering quality without going destitute?

To me the answer is for the audience to be more cognizant about purchasing work as directly from the artist as possible, whenever they can afford to. This is easy to convince people about in general, but more difficult once discussing how to support in specific ways.

I remember when Netflix was newer, a filmmaker friend of mine in Boston wrote a whole blog post doing the math on how Netflix is a no-brainer. In those years, Netflix was something like $5.99 a month for one disc at a time, $9.99 for three. The streaming service was just starting to roll out and was a bonus on top the regular subscription. Estimating 3-day mailing turnover at two discs at a time and one or two streaming options in between, he pointed out that he had access to a broader library of content than the sum of all his local rental stores for less than 50¢ a movie. Rental rates at that point were about $1, $4 for new releases.

However, now the landscape has changed, and Netflix is not only the only game in town. Most people aren’t paying $7.99 for a single streaming service, they’re paying $15.49 for a standard plan w/o ads. Add Hulu, $14.99. Amazon Prime, $14.99, Disney+, $10.99, on and on, all while Netflix has discarded its DVD library.

The average American household subscribes to 4.7 different streaming services. At, say, $12 a pop, that means they’re spending $56 and change a month. This article calculates $47. Even if they are streaming a movie every day, or three one hour episodes, or 5-6 half hour episodes (a normal single DVD’s worth of content) which most people don’t, they’re spending about $1.5 per movie, or more than it used to cost to rent. That number quickly goes over the $4 threshold once you remove the 1 per day whales and get the sort of person I assume most are like, who sit down to watch something 3-4 times a week.

At that point, renting individual movies or episodes from Vudu or Amazon (their non-Prime selection) is cheaper than subscribing to any service. If you’re okay with ads, you can use stuff like Freevee, Tubi, and PlutoTV. In my experience these sorts of services are somewhat less algorithmically walled off in terms of the content they place on the front page, but more importantly if you know what you’re looking for you can find a ton of great stuff that isn’t on any of the subscription-based streaming services.

I would argue that you can probably view 99% of anything you want to see by having an Amazon Prime account and supplementing with Vudu rentals. And those services typically have older classics and new independent features than any given other streaming service. So really, your monthly film and television costs shouldn’t pop up above $20 unless you’re a super binger.

But, if you’re like me and the type that does want to put in the extra investment on truly artful work, then I find the real game is in streaming services that curate content for specific audiences. So you can have genre services like Shudder for horror or Crunchyroll for anime, or indie services like Sundance Now for “prestige” indies or SlamDance Channel for underground indies, or international arthouse cinema from Criterion Channel or Mubi8.

The fun fact about all of these services is that they’re cheaper, sometimes even half the price, of the mainstream mass audience services. I’m not sure they solve the pay issue for filmmakers but they do provide better exposure and engagement for them than the other sites. I’ve seen a couple of filmmakers who were presented on Mubi or got their features onto Tubi were very happy with their experiences.

So as I see it, it’s sensible and costs less to rent the studios movies and television you want to see from Amazon or Vudu, and subscribe to one or two curated services that give you specialized content you personally take to. Rather than more Peacock’s (NBC Universal) and Max’s (HBO and Warner Brothers) and so on, I’d rather see Shudders for romantic comedies or action adventures, SlamDance Channels for experimental or cult cinemas, and the producer/distributor exclusive walled garden pipeline broken up under the same antitrust laws that required movie theatres not be owned by studios (repealed, but in my opinion should be reinstated).

Distribution Models I Like

My favorite model for a distribution platform is BandCamp.

BandCamp takes a flat 15% fee off direct purchases of digital tracks or albums up to $5000 USD, at which point the rate drops to 10%. Fees for physical items are always 10%. The rest goes to the musicians or label.

The original price is set by the artists or labels, and if they want to offer their work for free, there’s a pay-what-you-please option. The content can be free to play on the site and then purchasable, or locked until purchase, with previous or samples. On much of the free-to-play music, the audience can listen to the album twice before the content locks and BandCamp asks you pay to continue listening to it.

BandCamp also features subscription options for individual artists or labels using Stripe that operate just like Substack subscriptions.

This all strikes me as a robust and fair model for artists to charge what they feel their work is worth, audiences to pay as much or as little as they please, the platform to make enough to cover hosting and development costs, and for engagement to be more directly related to individual preferences and artist’s success9.

Filmmakers do not have a sufficient BandCamp-like platform for their work. YouTube ad share simply cannot cover the costs of production. Vimeo has a relatively good pay-on-demand service, but I personally find it difficult to find work and it doesn’t allow free previews like BandCamp does – either things are paid or locked. Open streaming services like Amazon Prime require too many watch-hours of viewership to be profitable and closed streaming services pay too little initial fees and have the same watch-hour issues, as discussed above. Indie streaming services typically are curated so hard to get into and also rarely make a lot of money themselves to share with the creators. Platforms like Patreon invest audiences in individual creators but restrict and limit the opportunities for individual works to find their distinct audiences.

The BandCamp model also makes no distinction about length-format of content in a way I find appealing. It’s extremely difficult to sell a short film either to distributors or to audiences, and it’s basically never profitable. Short films are normally offered for free to build an audience for the filmmakers. And even as a fan of short films as an art unto themselves, I very rarely watch a short film more than once, so I understand the audience’s reluctance to pay for too many of them.

That’s why the idea of having short films available for free for a couple of plays before locking down and asking for a purchase seems like a great compromise. We filmmakers all know that most people will only watch it once and it’s better to get more eyes on the short film than expect profit from it, but it would be great to have an option for people to buy it, as well as a provision for potential superfans who keep returning to it to be nudged into purchasing.

The cons of BandCamp are that there aren’t many big labels that want to share 10% of their profits with a platform that hosts their work, and audiences don’t want to spend $10 for every album when they can pay $10.99 for a month of Spotify to listen to whatever they want. The result is that though BandCamp as a platform is super cool, it takes individual initiative and patience for the audience to find music they like and support it. They have to care.

Also BandCamp has no recommendation engines. Artists and labels can recommend other albums after purchase (again, much like Substack subscriptions), and there’s a bewildering and somewhat overwhelming front page widget that flashes every album that’s being purchased anywhere in the world in a stunning stream of thumbnails, but is that feature is only fun to watch, it’s not useful for finding music.

To me, this lack of a recommendation engine and other algorithms is a pro, not a con, of BandCamp: you find your music through friends and artist recommendations, they reach out to audiences through regular advertising or social media channels or groups, there’s a natural element of community and discovery. There isn’t only 500 albums BandCamp features that you can never dig past to access the rest of the library.

It’s still true that the vast majority of artists on BandCamp simply do not make enough money to “quit their day job.” However, at least that’s due to an honest lack of audience, talent, or marketing, or even due to not wanting to charge for their work; that’s more honorable than simply being undercut by the platforms’ rates and not having useful metrics for how many people are truly interacting with your work.

I’d like a BandCamp for filmmakers. Technically videos can be uploaded to BandCamp too, but the only real issue there is that people go to BandCamp for browse music, not movies. Having a FilmCamp offshoot, either as a part of BandCamp’s platform or as a unique company, would be stellar. Since video takes far more bandwidth than music, it would be understandable for the film specific platform to charge more like 30% on purchases, which is what the consignment rate for self-published work at Hastings used to be.

In lieu of a BandCamp for filmmakers, I look to filmmaker Scott Barley’s website as a model for self-distribution. His movies are available there in both formats playable on home systems as well as DCPs for cinema projections, at both consumer and institutional rates. I’m inspired enough by this model that I’m currently building my own website to host and sell digital copies of my movies myself.

Of course, the problem with selling directly off your website is there is no networking effect. Very few Internet users go to individual websites anymore. A filmmaker still would need to cast their souls into the black holes of algorithms and engagement arms race to be ‘found’ on social media. That’s another full time job, and most people are not great at it.

But nothing beats just going to the movie theatre. There’s no closer audience-engagement-to-filmmaker-success pipeline.

There’s no consumer welfare economic argument to be made there: a single ticket plus popcorn and soda costs more than a month worth of subscriptions for a handful of streaming services. My biggest worry is that there are fewer cinemas left, and they show fewer films, and those films are usually studio franchises, which audiences are abandoning, which closes cinemas, which reduces screenings, which requires the screenings be more sure-fire hits, which greenlights more franchise films.

Luckily there seems to be a rise in theatres like Alamo Drafthouse and Nitehawk that are expanding the model by including food and alcohol. The overall experiential aspect of cinema is being tweaked. Larger cities typically have independent and even non-profit movie theatres that specialize in bringing unique movies to audiences, and my personal experiences in New York City is that those cinemas are much fuller than the AMC and Regal auditoriums are.

However, there’s another long-term model that people in smaller towns or in close groups of local film fans may want to consider, a model as old as movies themselves: community cinema. All you need is a white wall and a projector hooked up to some speakers. These can be held in community spaces such as libraries and churches, or cheap and available real estate such as conference halls and parking lots. A group shares in the cost of paying an institutional rate or rental fee direct from a distributor, which is usually only a couple hundred bucks and sometimes less, and everyone brings their own snacks10.

You Are What You Eat Grow

When it comes down to it, it’s not true that “They don’t make good movies anymore.” The history of film has always contained an underlying three-way tug-of-war between studios trying to shore up costs and risks, against artists trying to express themselves while make a living, against audiences seeking novel, quality entertainment. A very quick rule of thumb though is that if something is cheap and convenient, it probably pulls the rope away from the artists. For a while the audience may feel they’re winning too, but if the artists fall, the audiences will start losing too.

I personally hold no animus against studios for trying to create dependably profitable blockbuster spectacles, streamers trying to provide a full library of content for an affordable subscription cost, or to the audience for seeking available and frictionless entertainment. All of these things are okay.

The key issue is that each of these things comes with costs, and sometimes those costs are obscured. The strikes are one attempt by unions to reveal the costs to the consumer and that the burden is often shouldered by the creatives themselves rather than shared with the studios or distributors. As new technologies such as Internet streaming or AI provide new opportunities to reduce costs and increase convenience, artists and audiences should benefit from those opportunities too.

The artists know the issues, and that’s why they do things like strike, or try to find alternative and unique methods of monetizing our work. But audiences can do their part by maintaining a curiosity about what other services and distribution options are out there, by being willing to pay a premium for premium content, and by always asking themselves how directly their payment for a movie or television show may be directed to the creatives involved in making it.

“They” don’t make good movies anymore, we do. And we’re looking for your support.

This is my ironic takeaway of Robert McKee’s Story, where he interviewed the brilliant filmmaker Robbe-Grillet and asked him how he could afford to make such abstract, non- or antinarrative films. Robbe-Grillet answered “I can only make $20million in ticket sales, so I keep my budget under $20million.” McKee then wrote that the further away from story you get, “your audience necessarily shrinks.” Rather than turning me away from the concept of adhering to story fundamentals, it inspired me to keep my budgets low.

And health insurance and pension compensation.

Another fun fact to be gleaned from WON: No titles are available from before 1954.

A note that that doesn't necessarily mean that Blockbuster had 10000 distinct titles. Usually new releases would get a couple hundred copies that would slowly purge down to one or two regular rentals.

We could set the time limit any length we wanted, but six months was a fairly good compromise between too many and too few.

Another specific illustration: I just retrieved my copy of Unseen Cinema, a collection of experimental films from around the world produced between 1894 and 1944, from storage. That boxed set was available on shelves all over the midsized city I grew up in – I’ve only seen it on sale at Anthology Film Archives in New York City and none of it is available for streaming. An entire half-century of cinema is nearly gone for modern audiences to watch after being widely available just 15 years ago.

Genuinely interesting to see that even in the depths of the pandemic when film production was essentially completely shut down and was extremely challenging to do with social distancing and new COVID protocols, the United States still made about as many movies as it produced normally in 2001.

If you live in the UK, Ireland, or India, or in the cities of Chicago, Denver, Los Angeles, New York, Portland, San Francisco, Seattle, Berlin, Munich, or Frankfurt, Mubi also has a Mubi Go option that provides you weekly free tickets to curated movies in theatres. I use it and it’s highly recommended: you only have to go a little less than once a month for it to pay off the additional subscription price.

An in-the-weeds technical cool thing about BandCamp is that purchasers can also choose different formats of digital files, from large, uncompressed, full quality files to compressed, small, fast-play .mp3s. A filmmaker-friendly BandCamp would then offer streamable .mp4s and multiplatform accessible filetypes alongside industry standard DCPs, etc.

This section does not include film festivals because that’s an entire other essay probably as long, if not longer, than this one. The short of it is that festivals rarely pay screening fees and are more marketing / network events for filmmakers than distribution. Festivals are considered a cost of filmmaking. Whereas I would encourage general audiences to go to festivals to support filmmakers’ work, no filmmaker has ever made their livelihood on the festival circuit.

Thanks so much for this DB and I hope we get more posts and analysis from you in the weeks and months ahead. Thoughtful, accurate, and fuel for the future.

I love the idea of a FilmCamp. The hard-to-find problem would probably resolve itself if critics were incentivized (small royalties?) to create their own lists of movies to watch.

Also, when you mentioned Bandcamp allows people to upload movies, they've got a 500mb size limit, so that precludes features. :(

But, I still think the idea as a concept is good.