Attentive readers will see the name

and spot the ‘Hugo’ in the title and be reminded of his previous 7,000+ word STSC fiction contribution An Unexpected Guest.Well he’s here again with another immersive and exquisitely written story, ideal for some quiet weekend reading.

Enjoy.

TJB.

I stretched the wings, leaped down the stairs, and exited the domicile, home sweet home, la casa mia, et cetera. The air was cool and crisp, like a splash of seltzer chasing an espresso, and the sun just getting into full swing. It was some weeks before the visit of my Uncle Baxter, an adventure of which you have no doubt heard.

I say no doubt but there is doubt, no doubt. Why shouldn’t there be? I can’t keep track of both of my readers. You might be one or the other, and if you’re the one and not the other, the other one that read about my meeting with Uncle Baxter, well then you’ve never heard of Uncle Baxter, or me, Hugo Davenport, and I would almost go so far as to say that you’re not even a reader of mine because you’ve never read me before this. This. This word. Which means I’m writing for one reader (yes, you) who’s impossibly bored by this precis and t’other who’s lost at sea in a fog so thick he can write his name in it without so much as the hint of a lighthouse to guide him past the rocky shoals into a safe harbor.

Well, there it is new, or quite possibly, old, reader. Welcome back to Florence, that little college town home to the aptly named Florence University. How they ever came up with that corker of a name is beyond me. The town is nothing like its namesake in the old country except for the fact that both feature a center of learning where learned men such as myself go to learn and to see to it that others learn so that they may come and learn to learn and become learned men (and women, of course, no prejudice or discrimination intended it’s just how it goes: when one is a learned man one speaks of oneself as a learned man and of learned men generally. It goes without saying) and teach more students to become learned. A beautiful cycle, not unlike the circle of life that British crooner went on and on about in that nature documentary.

Certainly learned men learn at our humble university but more often than not, we learned men do all we can to avoid learning, having learned instead to put off that day, Judgement Day (yes, spelled with an ‘e’) until tomorrow or quite possibly the next day.

It comes with the territory. And Judgement Day sometimes comes sooner than you think.

There I was sipping a morning cappuccino outside the Jittery Scholar watching cars trundle past on the tree-lined street when up popped Dimmy, or Steven Dimmick as his mother calls him. Still calls him as far as I know. Dimmy was a first-year Classics student and we rubbed elbows around the office and at the occasional get-together.

When I say “up popped” what I mean is that Dimmy drifted past me almost in slow motion doing his very best impression of a sloth, except not one of those happy sloths that they feature on children’s animal programs but rather a dour, down in the dumps sloth preoccupied with earthly cares.

“Hey, Dimmy. Why the long face?”

He looked at me, agony painted across his round, youthful face and shining eyes. “Oh, hi Hugo. I didn’t see you there.”

“Want a coffee?”

“No, I think it’d just wake me up even more to the hell I’ve prepared for myself.”

“Oh? What happened?”

“The sky is falling. The walls are closing in.”

He often talked like this when some crisis arose.

“That sounds rough.”

“Ha!” He let out one of those mirthless laughs you hear so much about in novels. “Rough doesn’t begin to describe my situation.”

“Well, just start telling me all about it and I’ll see what I can do to help.”

He sighed. “You know how one of us is presenting each week in Martial?”

I nodded. I was familiar with the scheme. Professor Russell, a stern high-minded English woman of about 40, had each of us pick one of Martial’s epigrams to analyze and then present on during class, preparatory to developing ideas for our term papers due, as the name would suggest, at the end of the term.

Not only was it a paedagogical tool, it was also a convenient way for the prof. to waste thirty minutes of class time each week (although she would never admit it and would likely storm off, nose in the air, at the merest whiff of a suggestion that that’s what she was doing).

I had volunteered for the last slot sometime in April. Dimmy the too-eager beaver had volunteered for an early slot in February.

He continued, increasingly dejected with each passing word. “It’s my turn today and I forgot. Well, first I put it off—”

I nodded sagely, recognizing the young scholar’s first mistake, one so common to us all.

“— then since I’d put it off, I forgot.”

He looked small and frail like a snail without its shell shrinking down into any available crevice in an effort to hide itself from the world.

“That tends to happen. Cheer up,” I said, slapping him on the back, “just go in head high, push through, and it’ll be over before you know it.”

His eyes registered panic. “I can’t! There’s no way. You have to help me.”

“How am I supposed to help you? I can’t do your presentation for you.”

“No, but you could stall Professor Russell. Just get talking about Martial or something. Do you know of any interests she has? Just keep her talking and take up the time for my presentation.”

I scratched the old nog. “That’s a tall order. She’s not one to get sidetracked easily. And even if I do, class is almost an hour and a half. That’s a long time to keep her going. Why don’t you just skip class? Make up an excuse. Say you’re sick or something. ‘Under the weather’ is the phrase I like to go with. This isn’t high school. No one’s going to send you to detention for skipping school and she’s not going to check up on you at home.”

“I can’t skip. She’ll know for sure. I couldn’t handle the shame of just not showing up.”

“Nothing for it then but to go down fighting.”

“I’ve got nothing to present though.” He looked at me, a feverish kind of light in his eyes. “Please, you have to do something.”

It was my turn to sigh. “Dimmick. Dimmy. Dims.” His eyes pleaded with me. He had that still youthful, still hopeful kind of face and it was doing its damndest to sway me.

I’m not an obliging nephew, or even a good nephew. I am, however, a good and obliging friend. Never leave a man behind, or something like that. Whatever the grad school equivalent is.

I swayed. Like an ash on the mountain tops, the woodsmen surround it and begin with their axes chopping each in turn until finally with a shiver from the very tip of the highest branch the tree sways and falls, collapsing under its own weight.

I toppled.

“I’ll see what I can do.”

“Thanks, Hugo. I owe you.”

“Yes, you do.”

_______________________________________________________________________

I sipped my cappuccino and puzzled over the problem before me. Professor Russell was a tough nut to crack, as far as nuts go. Not quite as hard as a completely enclosed pistachio without the slightest opening but harder than a whole peanut with crumbly yielding exterior.

I continued my ruminations as I walked to the office.

John Wanlock, one of my fellows, was sitting at his desk near the window. John was tall and stringy with a sharp, intelligent face which at the present moment was bent examining some tome.

I sat down heavily and scooted the wheeled chair over to the side of his desk, the chair emitting piercing squeaks beneath me.

I grunted. “Hey.”

“Hmgh.”

Our greeting ritual concluded, I proceed to business.

“I need your help. Well, more accurately, Dimmy needs your help.”

“What’s he done now?”

I related the young man’s plight and my plan.

“So, will you help young Dims?”

“You know, when you call him that it makes him sound not so bright.”

“Well, I suppose he’s not. He is the one who didn’t prepare.”

“I’m standing right here!” Dimmy said from behind me having walked in unnoticed.

I shushed him. “Not now. Mommy and Daddy are talking.”

“He should do his work,” said John.

“Oh that’s not fair. Like you never put off an assignment for a class you didn’t like, or even for a class you did like.”

“I thought you just said he was dumb for doing that.”

“And aren’t we all a little dumb sometimes? The boy’s hurting, John, he needs your help.”

“Why are you trying to save every MA student that comes through here?”

“I’m just trying to be a good colleague and steward to these young men and women. Does a shepherd abandon the lamb that wanders? No, he guides that lamb by hook or by crook until it becomes a productive member of the flock, helping it, not leaving it for the wolves.”

“Alright, get off your high horse—

“Sheep.”

“Get off your high sheep. I’ll help if you’ll leave me alone.”

“Deal.”

“What do you want me to do?”

“We’re going to stall Russell’s class.”

John looked alarmed. “What? No, no. She’ll see right through us. ”

“Not if we’re clever about it. Come on, what can’t two broad-shouldered, long-fingered young men like us not do?”

“Why do you have to be weird and talk about my shoulders and fingers?”

I sniffed. “It’s not weird. It’s a compliment.”

“So what’s the plan?”

“I’m going to engage the dear prof. in clever banter and you’re going to help.”

He looked nonplussed. “Clever banter isn’t going to be enough.”

“You’re right. That’s why banter is just phase one. Phase two is substantive banter.” I paused for effect.

John looked at me blankly.

“What does Professor Russell like above all else?”

“Martial?”

“No,” I said, drawing closer. “I have a secret weapon.”

“What?”

“Professor Russell likes soccer.”

“Soccer?”

“You know, the sport with two teams, eleven a side, played on a large open field, a net at either end, played with an inflated ball, the goal of which is to put the ball into the opposing team’s net, a game invented by the British which they still call football.”

He looked at me with murderous eyes. “I know what soccer is.”

“Ah. You seemed to be nonplussed but you’re just plussed. My mistake.”

“You can’t be plussed. It’s just ‘nonplussed.’”

“You can be whatever you want, use any words you want. Shakespeare made up words all the time, words like dauntless, lackluster, emolument, breast.”

“Shakespeare did not invent the word ‘breast.’”

“No, I suppose I stand corrected. But it’s a good word, eh?” I spoke slowly. “Breast. What do you think, Dims?”

“Yes, I like breast.” He immediately turned red.

“Haha, I knew you did, you devil. Just don’t let Professor Riggs hear you. He’ll try to show you his wife’s.”

John grinned. “Goddammit, Hugo.”

“It’s not my fault. He brings them up every chance he gets! It’s like the story in Herodotus—Candaules showing off his wife to Gyges. And where did Candaules end up? Six feet under with his bosom buddy on the throne, that’s where. Anyway, you get the point. Plussed as you are about soccer, we continue on. I know she’ll want to talk soccer in class and I’ve got a surefire way to see that she does. She won’t be able to help herself.” I winked at Dimmy. “Here’s what we do…”

______________________________________________________________________________

I walked into class side-by-side with John. Dimmy was already there plus a few other first, second, and third-years. John and I made six.

I took the room in at a glance, sizing it up. I measured the space from the door to the windows, from the chalkboard to the back, the space between windows, the height and width of the chalkboard, the average space between desks, the average space between occupied desks, the distance from the table at the front to the first row of desks and, most importantly, the distance from the desk I intended to occupy to the door and the closest window.

I filed this information away for future ref.

Dimmy sat by the window in the back. We’d agreed that the greater the distance between him and Russell, the better. The other three MAs were scattered around the room in the neutral zone behind the front row of desks, which was empty.

Too busy taking in the room, I missed what John said. He was babbling about soccer, really getting into it and saying something about Johan Cruyff.

“What?”

“I said, Johan Cruyff was the greatest player of all time and Pele can suck it.”

I spoke under my breath. “Can we keep it in this century, John? Jesus, it needs to be relevant to Professor Russell—

“Yes?”

I whipped around. Professor Russell was standing in the doorway.

“I thought I heard my name,” she said in her very proper southern English accent.

“Hi, professor. I didn’t hear you behind me.”

“Shall we?”

“Certainly, certainly, by all means. Yes.”

I settled into the first row, John next to me. Professor Russell slung her bag onto the table and began arranging books and papers here and there according to an order and system that only she understood.

I studied her intently. Mid-forties, wide-set eyes behind dark-rimmed glasses, smartly but casually dressed. A streak of gray in her black hair. A handsome face that gave little away. She was not one to wear her heart on her sleeve but preferred to keep it tucked behind her left breast, the place where four out of five doctors recommend you keep your heart.

Still shuffling papers, she scanned the classroom in a glance. “How was everyone’s weekend?”

Desultory nods and mumbles followed.

I thought I’d start to warm her up with some tactful compliments directed toward one of her favorite authors. “Fine, professor. How was yours? Do anything interesting? Read more of our dear old Martial?”

She smiled slightly. “No, I didn’t get to Martial this weekend, sadly. I had much more mundane concerns to deal with. A couple grant proposals due and lectures for my other classes. I did get out a bit though.”

“Oh, to the park or somewhere?”

“Yes, actually. I enjoy reading in the park whenever I get the chance.”

“Yeah, I find the fresh air does the body, mind, and soul some good, doesn’t it? Don’t you agree, John?”

John started at his name. “What? Oh, yeah, for sure.”

“It really makes you think about what Horace said about a mens sana in corpore sano. Something we should all take to heart.”

“Juvenal,” Professor Russell said.

“Eh?”

“It was Juvenal. Orandum est ut sit mens sana in corpore sano. You should pray to have a healthy mind in a healthy body.”

“Oh, right, right. Juvenal. What I mean to say is that reading out in the fresh air really helps with the mens sana but I find that the best way to keep the corpore sano is physical activity. I love soccer, played this weekend in fact.”

“Oh, really?” Professor Russell said, flicking through the papers with a disinterested finger.

“Y-yes and I watch whenever I can, highlights mostly, getting soccer on streaming costs a fortune, plus the Euros and the World Cup when they come around.”

“Hmm. That’s nice, Hugo. Well, let’s get started, shall we? Steven, you have a presentation for us today, correct?”

I turned my head so I could just see Dimmy out of the corner of my eye. He was staring out the window longingly, hoping as a small child might that the rest of the terrifying, frightening world that he was ignoring would just disappear.

When Russell said his name it was like someone had set a time-delay firecracker off under his rear. Have you ever seen those nature programs, usually narrated by David Attenborough? There’s a hare in a barren wilderness. A few trees. The landscape covered in snow. Cut to a fox stalking the all-white hare. The hare lifts its head. Its nose twitches, once, twice. It hears the footstep of the fox, the barest whisper of fox paw on snow.

The hare leaps out of its skin and flails its legs trying to get purchase in the powder. Legs whirl, snow flies, and the fox makes a mad dash.

It was like that. I distinctly saw Dimmy’s legs make involuntary running movements under his desk while his eyes bulged and pingponged between the window and the door.

“Steven?”

“Ha, hmm, ah, yes, professor?”

“Your report. Which epigram was it that you chose?”

“Haha, well, about that—” He looked at me.

“Professor.” I said. “Professor, before we get to all that I was wondering if you might weigh in on a debate that John and I were having. I was saying that Messi and Ronaldo are overrated and that playmaking midfielders and backline defenders, Pirlo and Giggs come to mind, are the true heroes of soccer—”

John chimed in. “But I say strikers are most important. They put balls in the back of the net. I mean, what are you going to have midfielders and defenders just passing the ball around in a zero-zero tie all day? You need guys like Messi and Ronaldo and Mbape scoring goals, winning games, making the fans happy. Without the fans every soccer club just falls apart. They can’t all be owned by Saudi billionaires.”

“What do you think, professor?”

Professor Russell looked confused. “I don’t really care, Hugo—”

“Right. I totally agree. They’re overrated, not to mention overpaid. Messi and Ronaldo—”

“Enough. I don’t care about any of it. Can we move on to Martial now? I don’t know why I’m asking you for permission. Steven—”

I was flabbergasted. I’d laid out the bait and this prof wouldn’t bite. Soccer of the international or any other variety was not on the menu. I collected my thoughts, marshaled my resources, gave the little gray troops their marching orders.

“Of course, of course,” I said. “I was just reading some Martial this weekend—”

“Alright, Hugo. Since you seem so keen on speaking today, why don’t you give us your presentation on Martial?”

“Huh? My what?”

She looked at me intently, enunciating very carefully. “Your presentation on Martial.”

Here I began to get the feeling that something, somewhere had gone terribly wrong. I had begun with clever banter, well, certainly banter even if it wasn’t clever or witty, the banter that was slightly elevated small talk, the poor man’s badinage. Then I had gone for the proverbial jugular with Soccer Badinage™ between myself and John and delivered via an irresistible debate prompt.

The scheme should have come off without a hitch but instead it had come off the rails. I felt that I was missing some crucial piece of information, some key morsel that would explain the failure, but what it was completely escaped me.

“But it’s not for two months.”

She waved a hand airly and leaned back in her chair. She looked down her nose, eyes half shut, one eyebrow raised. “Oh, that’s alright. Just go ahead and do it now. You seem eager to offer your opinions on everything from weekend plans to soccer so why not add Martial to the mix? That’s not a problem, is it?”

I had two choices in that moment. Admit defeat, cower and crumble, beg and plead for my life, cry out that I was too young to die and that Steven, the rightful presenter, should be the one forced to set his neck on the guillotine and look down at the basket ready to catch his head. Or, gather the nerve of the Davenports, do as old Uncle Baxter might have done and grab the Martial-presentation-shaped bull by both horns and wrestle it to the ground with all my skill and training and intellect.

As I once told Uncle Baxter, I’m no quitter. If I was going to go down, I’d go down spouting nonsense about a long dead poet to help a friend.

“Of course, of course. May I?” I said, gesturing to the chalkboard.

“By all means.”

I stood up, mint-green Oxford Classical Texts volume of Martial’s Epigrams in hand. I took my position at the front of the class, book in one hand, chalk in the other.

Professor Russell shifted off to the side, scooting her chair into the no-man’s land between chalkboard and first row of seats. She looked on and I was reminded of the fox and hare analogy I used just above, except I was the hare this time.

Out in the crowd, Steven did a poor job of feigning disinterest in the proceedings as if his honor didn’t hang in the balance. John looked slightly sympathetic but entirely amused as if I had brought this on myself and he was going to enjoy whatever happened next. The others couldn’t care less what happened as long as they weren’t being asked to translate pages of Latin they didn’t prepare.

Like Jesus on the cross I was saving my flock by my delay.

Okay, maybe the Jesus comparison is a bit much.

Okay, yeah, it’s not maybe, it’s a bit much, but in my defense we Davenports were born with a high opinion of ourselves.

I flourished the chalk, raised it a hair’s breadth from the board, and started writing, reading out loud as I wrote:

Hic est quem legis ille, quem requiris,

toto notus in orbe Martialis

argutis epigrammaton libellis:

cui, lector studiose, quod dedisti

viventi decus atque sentienti,

rari post cineres habent poetae.

“What better place to start than at the beginning.” I looked at Professor Russell. “I hope it’s alright that I don’t limit myself to one epigram. I know one-point-one is a bit obvious and we’ve discussed it before but I’ll touch on others as well.”

She nodded and waved her hand lazily.

“Well then. Book one, epigram one. Allow me to translate: here he is, the man you read, the man you seek, Martial, known throughout the whole world for his witty little books of epigrams, a man to whom you, eager reader, have given the glory while alive and comprehending, glory which few poets have when they’re ash and dust.

“There we have it all laid out for us. The man, the book, the decus, glory, earned by so many poets but for so many only after they are dead. Right away we encounter a conflict inherent in Martial—see, even we use a writer’s name as a metonymy for his work—but he does it himself: he elides the gap between poet and poetry and presents himself as having earned decus from the fact that he is read throughout the world.

“But,” I held up a finger, “he contrasts this glory with the nature of his work: libellum. The little book, the trifle, the collection of witty sayings. This isn’t epic, Homer or Vergil, so while he takes credit for his work and boasts essentially of his earned glory, he presents his work as mere trifles not to be taken too seriously.

“Which brings me to epigram four of book one. The address to Domitian, the emperor himself. He says: ‘If by chance you read my little books, Caesar, don’t be so serious.’ He goes on to say that it’s all a joke, that Domitian should read his epigrams like he would watch a comedic play and he ends with the assertion: lasciva est nobis pagina, vita proba, ‘my poetry is impudent, my life virtuous.’

“Here we see Martial the poet—both of these poems present Martial himself as the speaker in the poem—arguing that it’s all just a joke and that no one, including the emperor himself, should be offended by what he says because one, as he already established in the preface, he won’t use real names, two, it’s all just poking fun which even an emperor should be able to look kindly on, and three, Martial the man himself is virtuous, so don’t come after him because it’s the epigrams that are crude or biting or insulting, not the man himself.

“Martial presents for our consideration the distinction between the artist and his creation and he muddles the issue by first saying ‘here he is,’ not ‘here is my work,’ then telling Domitian not to get angry with Martial because he’s a virtuous person and it’s just his poetry that’s offensive.”

I know, dear reader (yes, you), you’re saying to yourself, ‘What is this?’ I realize this is not what you signed up for but I wanted to give some indication of the lengths to which I went, and to which I’m willing to go, for a friend. And let me tell you, just like a church sermon given by a vicar who seems to not need to breathe, I went on for some time, ‘on’ being the operative word. Also ‘for,’ ‘some,’ and ‘time.’ I guess I could throw ‘went,’ and ‘I,’ in there as well.

I translated, I analyzed, I spun a cloud of Martial thoughts into golden thread. My audience was, if not quite enraptured, only slightly bored.

Finally, I concluded and waited for thunderous applause or at least respectful silence.

The silence came.

Professor Russell cleared her throat. “Very, um, impressive, Hugo. Thank you.”

I beamed. “My pleasure, professor.” I put down the chalk.

“Just one more thing.”

I didn’t like where this Columbo impression was headed.

“Was that really extemporaneous or did you plan that speech in order to waste our class time so that Steven wouldn’t have to give the presentation he clearly didn’t prepare?”

My stomach balled up and sank into the region of my body where you might more typically find my Achilles tendon. My mouth opened and closed repeatedly while I uttered what could only be described as the death rattle of a fish choking on a piece of spaghetti.

“Hi—hiyee—I, well, hmm, I, hmm.” I coughed. “So, it’s like this—,” I managed to say.

“Oh sit down, will you?”

“Right.”

Professor Russell checked her watch. “Steven, you’ll go on Thursday. Get it done this time. Hugo, you’ll draft your term paper and turn it in on Thursday. I should think ten pages would be a solid draft, don’t you?”

She gathered her things and left without waiting for an answer.

I felt a tap on my shoulder. “Thanks, Hugo,” Dimmy said. “We got found out but at least I get to go on Thursday instead of today. Oh, good presentation too.”

I grunted and waved a disinterested hand, too distracted by the thought of having to write my term paper in two days.

John chimed in. “Yes, good presentation, Hugo. Did you actually prepare?”

I scoffed. “No way. Who has time for that?”

“Well, you certainly got into the spirit of it. I especially enjoyed your choice comments on critics of Martial scholars and where they can stick their pens.”

“I don’t remember saying that.”

“Oh the rest of us do. You really got going. But I thought you were laying it on a bit thick when you said you’d name your firstborn Martial.”

I winced. “I have to go.”

________________________________________________________________

“Double espresso on the house, Janie. I’ve got a paper to write.”

The owner of the Jittery Scholar leveled a stare at me. “On the house? Coffee’s not free.”

“Well it should be after what your nickel’s worth of free advice cost me.”

“Oh?”

“Did you forget you told me that Professor Russell loves football and talking football would be an easy way to waste an entire class period.”

“No, of course I didn’t forget.”

“Well John and I talked and it did nothing. She wasn’t picking up what we were putting down.”

“You talked about football?”

“Yes.”

“American football?”

I recoiled. “What? No. She’s British. Football is soccer.”

“Yeah, she’s British. And she likes American football.”

To say I was stunned would be like saying the sun is hot. It doesn’t quite come close to the mark. My opinion of the good prof. had decidedly fallen several notches.

“Who the hell likes football?”

She shrugged.

I sighed. “I hate football.”

I gently placed two dollars and thirty cents on the counter, downed my double espresso, and walked slowly back to my apartment.

That punchline at the end really hit.

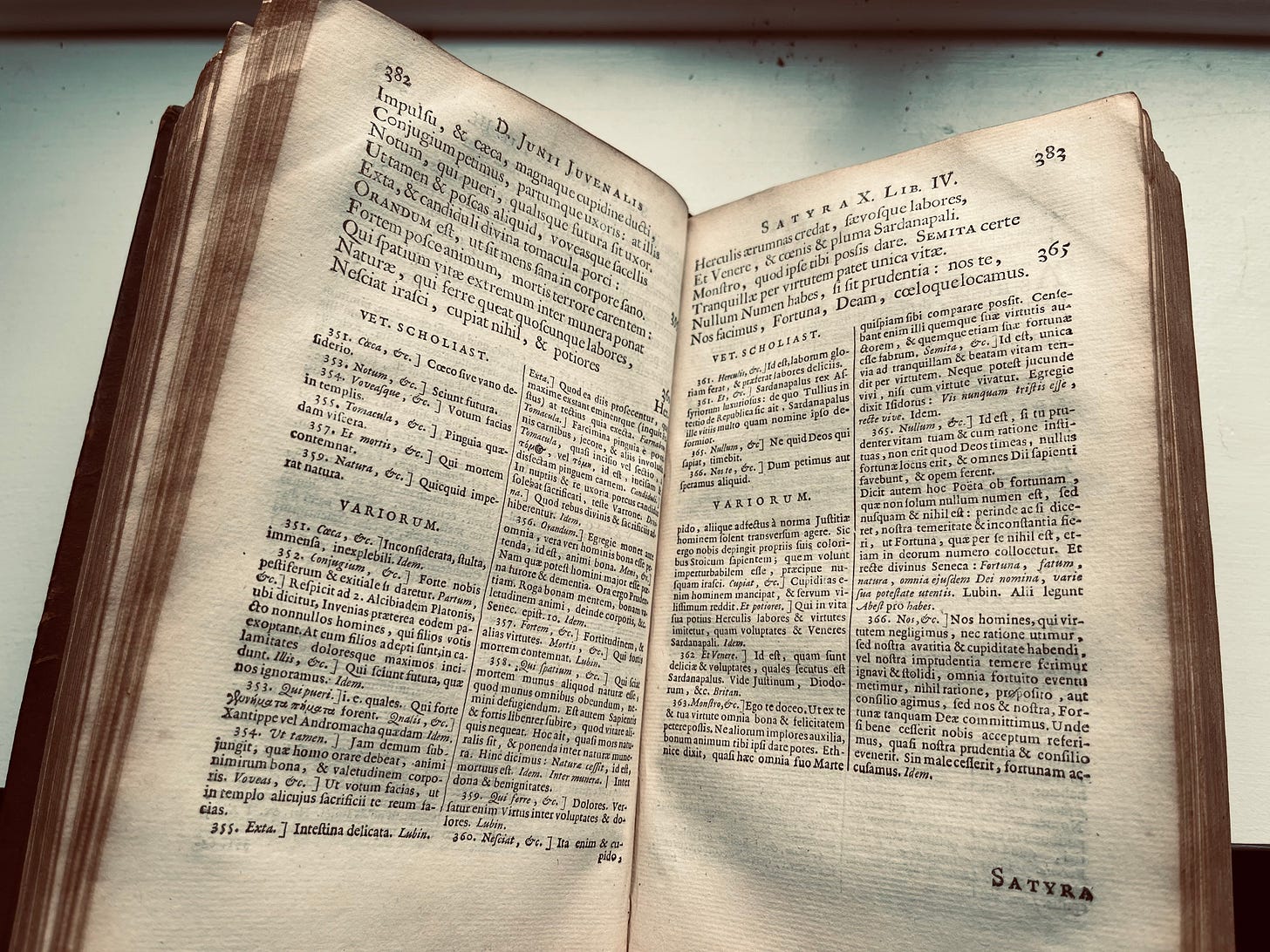

Bonus points to whomever can spot the Easter egg in the image.